The 3 Ways Data Centers Make Money (And What Each Means for Your Returns)

Every rack, lease, and megawatt tells a different financial story. Here’s how the three revenue models behind the world’s data centers actually make money.

Welcome to Global Data Center Hub. Join investors, operators, and innovators reading to stay ahead of the latest trends in the data center sector in developed and emerging markets globally.

This article is the 9th article in the series: From Servers to Sovereign AI: A Free 18-Lesson Guide to Mastering the Data Center Industry

Every data center may look the same from the outside: rows of metal shells, humming fans, and concrete perimeters.

But how they make money varies dramatically.

If you’re investing, operating, or competing in this sector, understanding these revenue models isn’t optional.

It’s the blueprint for how digital infrastructure converts electrons into earnings.

Revenue structure defines not only pricing and cash flow but also risk, churn, valuation, and investor appetite.

The wrong mix can sink a portfolio’s yield. The right one can compound returns for decades.

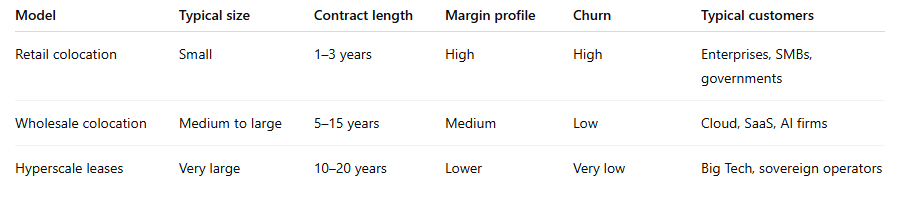

Each model (retail colocation, wholesale colocation, hyperscale leasing) caters to distinct customers with unique expectations, margins, and tenures.

Together, they form the foundation of the modern data center economy.

The three primary revenue models

1. Retail colocation

Retail colocation is the smallest unit of the industry’s revenue stack, but often the most lucrative on a per-rack basis.

Customers rent individual cabinets, cages, or small suites (sometimes just a few kilowatts of space) within shared facilities. They bring their own servers, and the operator provides the essentials: conditioned power, redundant cooling, physical security, and connectivity.

Pricing is typically measured per rack or per kilowatt, with add-ons like cross-connect fees, remote-hands support, and managed services creating incremental revenue.

Retail colocation attracts enterprises, financial institutions, government agencies, and IT service providers. Clients who want control over their hardware but can’t justify building entire facilities.

The tradeoff: higher margins but greater operational complexity.

Each customer has different compliance requirements, uptime needs, and connectivity setups. The result is more churn and higher touch, but also higher yields.

Equinix built its global dominance through this model. Its dense interconnection ecosystems (thousands of networks, clouds, content providers physically interconnect) allow it to charge premium rates. Interconnection itself becomes a profit center, not an add-on.

For investors, retail colocation resembles a multi-tenant office building in digital form: short leases, diversified tenants, and high margin per square foot.

It’s operationally intense but financially rich.

2. Wholesale colocation

Wholesale colocation moves up the scale: larger customers, longer contracts, lower unit margins.

Here, clients lease entire suites or halls, typically 1 to 20 megawatts of capacity, on 5–15 year terms. The tenants (cloud providers, AI startups, SaaS companies) install their own hardware while the operator provides the powered shell, cooling infrastructure, and connectivity pathways.

The economics shift from rack-based pricing to megawatt-based leasing. Cash flow becomes predictable, churn plummets, and the operator’s role simplifies: keep the facility powered, cooled, and compliant.

Margins per kilowatt are thinner than in retail, but scale offsets that. Operating costs drop, maintenance standardizes, and the operator’s exposure to customer volatility declines.

Digital Realty and CyrusOne refined this model, building multi-megawatt campuses with modular expansion. Developers often design flexibility into the site: subdividing large halls, adding power blocks, or extending fiber laterals as tenants grow.

Wholesale colocation aligns neatly with infrastructure fund strategies: stable cash flow, long-dated leases, and creditworthy tenants. Investors treat these assets like digital utilities, yield-driven, inflation-linked, and scalable.

For operators, wholesale colocation creates anchor stability within mixed portfolios, balancing the higher-touch volatility of retail.

3. Hyperscale leases and build-to-suit

The third model, hyperscale leasing, defines the top end of the market.

These are long-term, multi-megawatt agreements between data center developers and the world’s largest tech firms: Microsoft, Google, Amazon, Meta, Oracle, and increasingly, sovereign cloud operators.

Hyperscale deals often take two forms:

Leases: where the hyperscaler rents a completed facility or portion of a campus.

Build-to-suit partnerships: where the developer finances and constructs a site to the hyperscaler’s precise specifications.

Pricing is usually confidential and may include performance-based components tied to uptime or power efficiency. Tenures can stretch 10–20 years or longer.

Hyperscale tenants demand standardization (electrical topology, cooling configurations, sustainability metrics) across every region. Their aim is global uniformity at scale.

These tenants rarely churn. Once deployed, the physical footprint becomes integral to their global cloud fabric. For developers, a single hyperscale lease can anchor an entire campus, de-risking financing and attracting co-location tenants seeking proximity.

Hyperscale deals compress margins but deliver predictability. They also tie the operator’s success to the customer’s growth trajectory, aligning risk and reward in a long-term partnership.

The scale is staggering. A single Microsoft or Meta campus can exceed 100 MW, enough to power a city of 80,000 homes. Each campus then attracts an ecosystem of fiber carriers, cloud exchanges, and smaller tenants who pay premium rates for adjacency.

Hybrid and evolving models

The clean distinctions between retail, wholesale, and hyperscale are fading.

AI workloads have accelerated hybridization. A new category (GPU colocation or AI-as-a-service) is emerging, led by firms like CoreWeave, Lambda, and Crusoe. These operators sell compute capacity directly to developers, priced per GPU-hour, blending cloud economics with physical colocation.

Interconnection revenue, once a side business, has become a strategic profit driver. Equinix and Digital Realty generate hundreds of millions annually from cross-connects, bandwidth resale, and software-defined interconnection fabrics.

Even pricing itself is evolving. Some operators now explore performance-based or usage-based pricing, where customers pay for actual power draw or compute utilization rather than fixed rack allocations.

Retail and wholesale models increasingly coexist on single campuses. Operators design flexible zones: high-density retail suites near carrier hotels, wholesale blocks for hyperscale tenants, and powered shells reserved for future expansion.

This blend allows platforms to capture every layer of the demand curve, from startups renting 10 kilowatts to cloud giants leasing 50 megawatts, within the same geographic footprint.

Comparative revenue stack

Each layer plays a different role in capital structure. Retail drives yield. Wholesale anchors stability. Hyperscale unlocks scale and financing leverage.

Why revenue models matter for investors

For institutional investors, understanding how a data center earns its revenue is critical to underwriting risk and return.

Retail colocation yields the highest NOI per square foot but demands active operations—24/7 support, constant customer turnover, and frequent contract renewals. It suits platforms with operational expertise and dense ecosystems.

Wholesale colocation produces steadier IRRs and lower OpEx. Its long-term leases and credit tenants fit core and core-plus infrastructure strategies. Investors seeking stable income streams favor this model.

Hyperscale leasing de-risks new developments by securing anchor tenants before construction begins. A pre-leased campus becomes immediately financeable, attracting project finance lenders, sovereign funds, and REIT capital.

The most successful global platforms (Digital Realty, Equinix, NTT, ST Telemedia, Vantage) build portfolios that combine all three. The blend allows them to balance yield, duration, and risk while adapting to market cycles.

A retail-heavy portfolio benefits during expansion phases when enterprise demand spikes. Wholesale and hyperscale assets stabilize income through downturns.

The capital markets recognize this differentiation. Retail-oriented REITs trade at higher multiples due to recurring service revenue, while wholesale-focused players command lower but more stable valuations.

The shifting frontier: AI, power, and performance pricing

Artificial intelligence is transforming how data centers price and sell capacity.

GPU clusters draw enormous power, tens of megawatts per deployment, and their utilization patterns differ sharply from enterprise servers. AI tenants value time-to-power and thermal headroom over location or cross-connect density.

This changes pricing logic. In some cases, tenants pay for guaranteed megawatt availability even when idle, ensuring uninterrupted access to GPUs during training cycles. Others negotiate variable pricing tied to utilization, mirroring cloud economics.

Operators like CoreWeave have introduced a new hybrid: own the hardware, lease the power. They purchase GPUs and resell compute as a service, effectively capturing both infrastructure and workload margins.

This model redefines the boundary between data center operator and cloud provider, blending physical and digital business models into one.

Strategic implications

Operational intensity defines value creation. Retail yields depend on service density; hyperscale depends on engineering precision.

Power is the new pricing axis. The ability to deliver firm megawatts faster than competitors increasingly determines who wins deals.

Blended portfolios may outperform single-focus operators. Diversification across revenue models can mitigate both customer and market risk.

Interconnection compounds margin. Every cross-connect sold increases switching costs and network gravity, embedding tenants longer.

AI accelerates convergence. Operators who can flex between colocation and compute-as-a-service will command higher valuations.

The investor lens

From an investor’s perspective, each revenue model represents a different risk-return profile:

Retail: operational alpha through service differentiation and network density.

Wholesale: contractual alpha through stable leases and tenant credit.

Hyperscale: structural alpha through scale, financing leverage, and strategic partnerships.

The most sophisticated investors now evaluate platforms not by asset count but by revenue composition. A 100 MW portfolio dominated by hyperscale leases may yield less annual NOI than a 50 MW retail-heavy one, but with far less volatility.

Funds like Brookfield, GIC, and Blackstone are building layered exposure: high-yield retail assets for cash flow, hyperscale JVs for long-term stability, and development projects for capital appreciation.

In emerging markets, these distinctions are even sharper. Power scarcity, permitting delays, and regulatory risk make pre-leased hyperscale developments especially attractive. Anchor tenants such as AWS or Microsoft can de-risk entire projects, enabling financing from DFIs or sovereign wealth funds.

The takeaway

Data centers are no longer just about square footage or server count. They are structured financial products wrapped in concrete and copper, with distinct revenue mechanics, lease terms, and risk profiles.

Understanding how they make money (by the rack, megawatt, or megaproject) is step one in mastering how digital infrastructure scales, monetizes, and attracts capital.

Every revenue model is really a philosophy of operational risk.

very good article