Regulation As Alpha: How Smart Fiber-to-DC Capital Turns Friction Into Moats

The Real Bottleneck in Digital Infrastructure Isn’t Demand or Capital, It’s Regulatory Time, and Smart Investors Are Weaponizing It.

Welcome to Global Data Center Hub. Join investors, operators, and innovators reading to stay ahead of the latest trends in the data center sector in developed and emerging markets globally.

The deal that looked perfect until the permits arrived

The first sign of trouble in FTDC projects isn’t demand or capital it’s the administrative machinery that governs whether anything can move at all.

On paper, the project was flawless. A global fund secured industrial land at the edge of a fast-growing metro, between two hyperscale-ready power corridors and near subsea cable landings. The plan: a 120MW campus linked by a fiber-rich ring connecting the CBD, cloud zone, and industrial district.

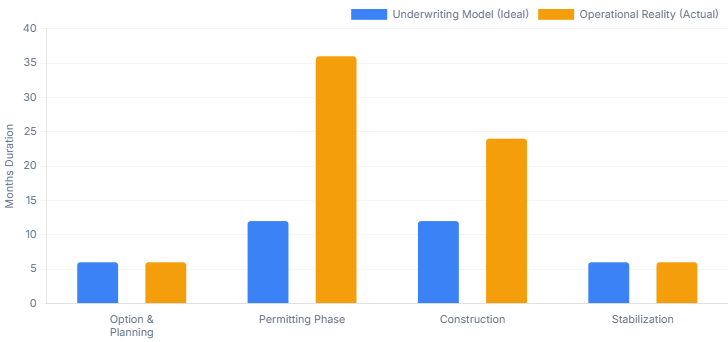

The underwriting model assumed three years from option signing to stabilized income. Then the permitting reality hit.

Trenching approvals were divided among five municipal offices, the proposed route triggered state environmental review due to a protected watershed, and national authorities initiated security and foreign-investment assessments tied to a defense-sector tenant and the sponsor’s foreign ownership.

As these layers accumulated, a three-year development window expanded to five or six. Contractor demobilization, material repricing, and rising interest carry eroded the economics, leaving the project with an IRR reduced by more than a quarter and several missed refinancing opportunities.

This is the new normal.

The story is not about one unlucky deal. It is a structural lesson: in the fiber-to-data center stack, regulation has become the real capital allocator.

Where regulatory complexity is really coming from

Investors like to treat regulation as a box-ticking exercise. In FTDC, that is fatal. The friction is systemic and multi-layered.

First, permitting has become the quiet driver of schedule overruns. In many markets, planning approvals, environmental reviews, right-of-way negotiations, interconnection studies, and security clearances can absorb up to half of an FTDC project’s timeline. Sponsors that treat construction as the bottleneck miss the real constraint: administrative processes that move at uncertain speed.

Second, data sovereignty has turned jurisdictions into isolated digital markets. With most countries now enforcing localization rules, FTDC projects must be underwritten as legally bounded sub-markets rather than regional networks. Routes that once operated as cross-border corridors now function as national or sub-national chains with distinct compliance demands.

Third, environmental and land-use rules have moved to the center of the FTDC model. National legislation and local zoning now introduce additional layers of approval, while data centers face growing scrutiny over energy use, water draw, heat rejection, and carbon intensity. In some power markets, special tariffs and minimum-take requirements for large loads shift more grid-cost risk directly onto data center customers.

Finally, national security overlays rewire ownership and control. FDI screening frameworks increasingly treat fiber networks and data centers as critical infrastructure. Reviews can impose board-composition rules, data-access restrictions, mandatory ring-fencing of sensitive workloads, and in some cases ongoing monitoring with real teeth.

Why fiber and data centers are now treated as strategic assets subject to FDI screening mirrors dynamics described in this review of how AI infrastructure has crossed into state-level power considerations.

The result is not “a bit more paperwork.” It is a structurally different asset class.

The numbers behind regulatory drag

When you quantify the friction, the scale becomes undeniable.

FTDC routes routinely require USD 60,000–120,000 per mile depending on density, civil-works complexity, and topology. Payback periods stretch seven to fifteen years. That is a very long time to be wrong about regulatory assumptions.

Time delays are increasingly costly. Studies show data center projects stalled by permitting or interconnection bottlenecks can lose up to $14.2M per month once ready to deliver capacity. For equity, the impact is nonlinear: a one-year delay can cut IRR by over 25%, especially where leverage is high and revenue ramps are back-loaded.

Compliance is now a modeled operating cost. Fees for RoW, environmental and legal teams, plus ongoing regulatory reporting, can make opex significantly higher than before. In some regions, energy rules add fixed costs for example, one state charges data centers for ~85% of subscribed energy regardless of usage, reshaping risks for tenants and landlords.

Layer political drift on top changes to subsidies, trade restrictions, new localization rules and the asset begins to behave less like core infrastructure and more like a hybrid of policy arbitrage and regulatory engineering.

How policy is trying to catch up—and why it is uneven

Governments understand the consequences of regulatory drag. Their responses are inconsistent.

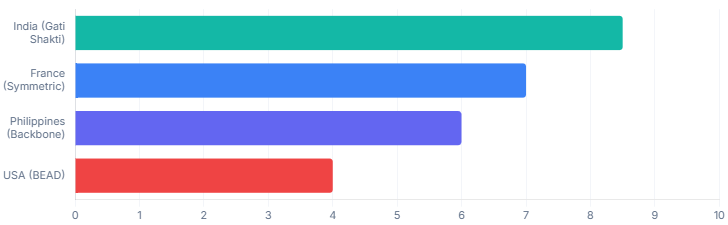

In the United States, the BEAD program’s USD 42.5 billion allocation underscores the push to close broadband gaps, but its early rollout revealed a fundamental constraint: funding cannot move faster than permitting. Subsequent federal adjustments have eased technology mandates and streamlined rules in recognition that process not capital was slowing deployment.

India provides a more targeted model of simplification. The Gati Shakti Sanchar portal consolidated all RoW applications into a single interface, and rule changes allowed contractors to file directly rather than relying on licensed operators. Early results show faster approvals and greater predictability for investors underwriting timelines.

Governments are also pursuing shared-infrastructure strategies. France’s symmetric fiber rules reduce duplicative builds, while Southeast Asian backbone projects such as the Philippines’ 1,245-kilometer network offer state-owned routes that private operators can use, shifting some regulatory exposure to the sovereign.

At the same time, environmental and energy rules are hardening. Moratoria, stricter efficiency standards, and targeted tariffs for large loads signal that governments will prioritize grid stability and sustainability, requiring investment to conform to their terms.

For investors, the key point is simple: Policy is moving, but not toward simplicity. It is moving toward sharper differentiation between coordinated and chaotic jurisdictions.

How the smartest capital is already adapting

Sophisticated FTDC investors have stopped waiting for clarity. They are compounding in the world as it is.

First, they have shifted where they take risk. Pre-acquisition work now includes detailed fiber and permitting diligence before any land is secured mapping dark-fiber density, testing right-of-way processes, stress-testing environmental and zoning regimes, and engaging national-security stakeholders early. Teams that follow this approach reject nearly half of sites that appear strong on power and land alone.

Second, they have changed what they control. Rather than relying on single-provider lit services, leading platforms secure dark fiber or long-term IRUs, ensure multiple diverse entrances, and design for route redundancy. On the power side, they lock in PPAs earlier sometimes before final site selection and increasingly develop on-site substations to reduce interconnection risk.

Third, they are scaling regulatory capability. Large managers now treat regulatory expertise as a core platform asset. KKR’s multibillion-dollar digital-infrastructure program and its USD 50 billion AI data center JV reflect deliberate investment in regulatory and government-relations capacity. Blackstone’s USD 70 billion portfolio and extensive pipeline rely on a global policy playbook that is now as central as its construction or leasing strategy.

Finally, they are rethinking where they play. Market selection now weighs regulatory predictability on par with latency, tax, and power pricing. Investors increasingly favor jurisdictions with reliable, time-bound permitting even at higher operating cost and deprioritize markets where regulatory volatility outweighs demand signals.

Why jurisdictional reliability has become an investable edge is reinforced by this examination of how regulation is increasingly being turned into alpha.

Alpha is shifting from financial engineering to jurisdictional engineering.

The emerging playbook: turning complexity into a moat

Regulatory complexity is not just a risk. It is a moat for the right kind of capital.

When permitting absorbs half the project timeline; when delays burn eight figures per month; when data must localize by law; when national-security reviewers can rewrite governance after signing then simply getting a scaled FTDC platform built, connected, and compliant becomes a competitive barrier.

The emerging playbook is clear.

Treat regulation as a first-order design variable. Build in-house regulatory and policy capabilities rather than renting legal advice episodically. Control the infrastructure layers where regulation bites hardest fiber routes, substations, interconnection rights. Prioritize markets where the state coordinates, even if coordination comes with higher scrutiny, because predictability compounds.

Laggards will continue underwriting glossy demand signals, cheap power, and easy land until they discover the real underwriting variable is how many actors can say no and how long capital remains trapped between their signatures.

For FTDC investors who want to compound through the coming decade, one lesson dominates: regulatory mastery is now the difference between stranded assets and the backbone of the AI economy.