Fiber Scarcity Is Redrawing America’s Data Center Map

As AI-driven compute pushes into secondary U.S. markets, the scarcity of fiber routes is emerging as the true gating constraintreshaping returns, timelines, and which regions can realistically scale.

Welcome to Global Data Center Hub. Join investors, operators, and innovators reading to stay ahead of the latest trends in the data center sector in developed and emerging markets globally.

The Event: Fiber as the Market Signal

The most revealing announcements in today’s data center market are no longer campus groundbreakings or power procurement deals. They are fiber route announcements.

When Zayo completed its 622-mile long-haul corridor linking Umatilla, Prineville, and Reno, the project was framed not as incremental telecom infrastructure but as a strategic enabler of cloud and AI workloads across the interior West. That framing signals a deeper shift in how infrastructure investors understand value creation.

The AI era has made clear that compute does not scale in isolation. It scales across geography. The physical paths that connect data centers now function as part of the compute stack itself. In emerging markets, the absence of those paths is increasingly the difference between investable capacity and stranded assets.

The Structural Cause: Power-Rich, Fiber-Poor Markets

For more than two decades, the U.S. data center industry benefited from an implicit hierarchy: connectivity was abundant, power was scarce.

Northern Virginia, Silicon Valley, and Chicago thrived because dense metro fiber rings and diverse long-haul corridors were already in place. New capacity could be absorbed without first building the connective tissue.

That hierarchy is breaking. The next wave of growth is moving into secondary and tertiary markets where land and megawatts are available but fiber density is structurally thin. The research shows that many of these markets are effectively “off-net.” Route diversity is limited, rights-of-way are contested, and redundancy must be constructed rather than purchased.

Why route diversity and rights-of-way are now gating factors mirrors cost and timing risks identified in this breakdown of the hidden economics inside fiber deployment.

Fiber is no longer a utility service layered on top of a site. It is a prerequisite for site viability.

AI as the Accelerant: Scale Meets Architecture

Artificial intelligence intensifies fiber scarcity through both scale and design.

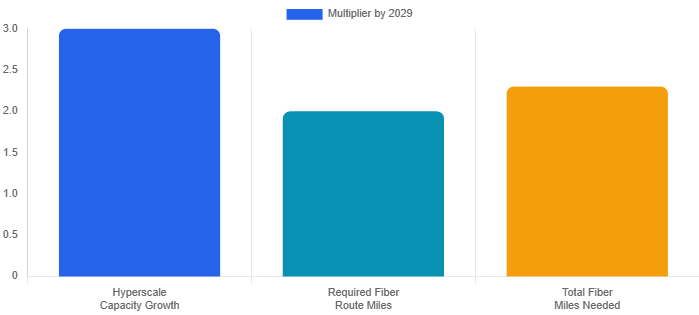

On the scale dimension, one forecast cited in the research indicates that supporting roughly a threefold increase in hyperscale capacity by 2029 would require approximately a doubling of U.S. fiber route miles and a 2.3x increase in total fiber miles. This is not incremental densification. It implies a national expansion of corridors, especially between emerging compute nodes.

On the architectural dimension, AI workloads behave differently from legacy cloud workloads. Training and inference increasingly rely on distributed clusters that function as a single system across multiple sites. That design multiplies east-west traffic within metros and drives demand for low-latency, high-capacity inter-regional links.

In this context, a data center without sufficient strand count, route diversity, and upgrade control is not AI-ready, regardless of how much power it has secured.

The Timing Mismatch: Fiber Lags Data Centers

The most acute investor pain arises from the mismatch between data center construction timelines and fiber delivery realities.

A well-capitalized campus can move from grading to shell delivery on a schedule that capital markets readily finance, particularly when pre-leasing is involved. Fiber infrastructure does not move at that speed.

The research highlights that fiber deployment is governed by permitting, environmental review, municipal sequencing, make-ready work, and the availability of specialized construction crews. In some jurisdictions, rights-of-way alone can introduce multi-year delays.

These processes are structurally incompatible with AI-driven deployment schedules that assume rapid monetization once power is available.

How administrative delays translate into execution risk is consistent with patterns observed in this analysis of how grid and infrastructure bottlenecks distort deployment economics.

Procurement and Cost Inflation: Balance-Sheet Risk

Procurement constraints compound the timing problem.

According to the research, lead times for fiber optic cable expanded to roughly 60 weeks at peak, compared to a historical norm of approximately 8 to 12 weeks. That shift fundamentally alters project finance assumptions. When material availability stretches by nearly a year, delays cascade through energization, commissioning, tenant fit-out, and contracted service delivery.

Cost inflation amplifies the risk. The research notes that fiber prices have increased by approximately 70 percent since 2021. At that magnitude, contingency budgets disappear, scopes must be renegotiated, and pricing assumptions come under pressure.

For fiber investors, higher prices appear supportive only until deployment slows and volumes compress.

For data center investors, low-cost land loses its appeal once the full cost of route creation and redundancy is accounted for.

The Financial Impact: Delay Becomes Loss

The economic translation of fiber scarcity is stark.

Delays on a typical 60MW U.S. data center can cost developers around $14.2 million per month. This turns fiber risk from a technical inconvenience into a key financial factor, explaining why leading platforms are increasingly willing to invest early and aggressively in connectivity. In the AI era, the cheapest time to address fiber constraints is before construction even begins.

At a global scale, the stakes are far higher. Research projects roughly $6.7 trillion in data center investment through 2030, including $5.2 trillion tied to AI workloads, which implies a need for about 156 gigawatts of capacity.

Meeting connectivity requirements alone would require roughly three million miles of network cabling and an equivalent of $150 billion in investment. While fiber represents a relatively small share of total capex, it can make or break the ability to monetize much larger investments in power and compute.

Policy Response: Partial and Uneven

Public policy is responding, but not in a way that guarantees near-term relief for investors.

The research highlights the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment program at approximately $42.45 billion. While BEAD is designed to extend broadband access, it affects the same supply chains, labor pools, and manufacturing capacity that data center fiber relies on. In the short term, public funding can intensify competition for constrained inputs.

State-level middle-mile initiatives are more strategically relevant for emerging data center markets. By subsidizing backbone infrastructure and promoting open-access models, these programs can lower the marginal cost of extending routes into new clusters. However, the research also underscores the volatility of the policy environment.

Permitting uncertainty, environmental challenges, and community opposition can introduce non-linear delays that are difficult to price into long-duration infrastructure investments.

Investor Strategy: Fiber as Core Infrastructure

The most sophisticated investors are not waiting for policy to resolve the problem.

They are restructuring underwriting, ownership, and contracting strategies around the assumption that fiber scarcity is structural.

Connectivity diligence now occurs before land acquisition, not after. Sites are screened on route diversity, proximity to dense rings, and the feasibility of adding new corridors. In many emerging markets, this process eliminates otherwise attractive parcels once the true cost and timeline of fiber delivery are modeled.

Ownership posture is also shifting. Rather than relying solely on carrier-provided services, leading platforms pursue dark fiber and physical path control where economically justified. The objective is not vertical integration for its own sake, but schedule certainty, upgrade flexibility, and security for latency-sensitive workloads.

Procurement has become a competitive advantage. Multi-year supplier relationships and forecast-based allocations are replacing spot-market purchasing. In constrained environments, the ability to guarantee cable availability and construction capacity can be the difference between winning and losing hyperscale leases.

Finally, financing structures are adapting. In emerging markets, speculative fiber is increasingly unbankable. The research points toward anchor-tenant models and long-duration contractual frameworks that convert builds into infrastructure-like cash flows. Fiber projects now resemble contracted utilities rather than growth experiments.

The Investor Lesson: Connectivity Decides Winners

The core lesson for fiber investors in emerging U.S. data center markets is uncomfortable but clear.

These markets are not low-cost expansions of legacy hubs. They are environments where investors must often build the enabling layer before capturing enabling-layer returns.

Route scarcity is not a temporary bottleneck. It is becoming the market structure for the rest of the decade. Investors who continue to underwrite fiber as a secondary consideration will misprice risk and misjudge timelines.

Those who treat connectivity as strategic infrastructure worthy of early capital, deep diligence, and structural control will determine which markets scale and which remain footnotes in the AI buildout.

In the next phase of the U.S. data center cycle, power may attract attention, but fiber will decide outcomes.