Does Oracle’s Cloud Launch at iXAfrica Reprice African Data Centers?

Hyperscaler anchoring and the structural shift in African data center valuation

Welcome to Global Data Center Hub. Join investors, operators, and innovators reading to stay ahead of the latest trends in the data center sector in developed and emerging markets globally.

For over a decade, African data centers were treated as speculative infrastructure demand seen as long-term, fragmented, and price-sensitive, with power as the main risk. Hyperscalers were considered eventual, not immediate, customers.

That framework is now shifting. Oracle’s launch of Kenya’s first public OCI region at iXAfrica isn’t just a Nairobi milestone it signals a real-time change in risk profiles, capital structures, and valuation logic for African data centers.

The question isn’t whether Africa is “ready” for hyperscale. It’s whether this deployment will reprice the entire asset class.

Latency Play to Balance-Sheet Signal

Most commentary around African cloud regions focuses on latency and data sovereignty. Those benefits are real, but they are not decisive for capital.

What matters more is what this launch says about hyperscaler willingness to underwrite African execution risk.

Oracle did not test Kenya with an edge node or limited local zone. It committed to a full public cloud region, placing core compute, storage, and database services inside the country. That decision implies confidence not just in demand, but in long-term operational stability, regulatory durability, and partner quality.

For investors, this is a balance-sheet signal. Hyperscalers only place regions where failure is not an option. Once a region is live, exit risk disappears. Capacity becomes strategic infrastructure; not discretionary IT spend.

That shift alone alters how cash flows should be priced.

This transition where hyperscaler commitment converts speculative capacity into strategic infrastructure follows a pattern already visible in other African cloud deployments, as analyzed in Will Vodacom’s $1B Google Cloud Bet Rewire Africa’s AI Market?.

The Colocation Partner as the Asset

Equally important is how Oracle entered the market. Rather than building a proprietary campus, it anchored its cloud region inside iXAfrica’s NBOX1 facility the same colocation-as-platform model used in Northern Virginia, Frankfurt, and Singapore.

The implications are structural. In this model, the hyperscaler takes on demand risk, while the colocation platform handles development and operational risk.

The platform gains long-term contracted utilization while keeping the option to add tenants, services, and expansion phases. This compresses risk in ways African data centers historically haven’t seen.

Instead of merchant capacity chasing uncertain enterprise demand, hyperscaler-led absorption shapes the capital stack, pushing valuation frameworks toward global hyperscale norms.

Power Stops Being the Discount

Power has long been the justification for African valuation discounts. Grid instability, diesel dependence, and carbon intensity were used to explain higher required returns.

Kenya breaks that logic.

With over 90% renewable generation, anchored by geothermal and hydro, Kenya offers a grid profile that many developed markets cannot replicate without bespoke PPAs. For a hyperscaler under Scope 2 pressure, this materially reduces complexity.

For investors, the effect is twofold. First, operating risk declines. Second, ESG-adjusted capital becomes cheaper and more abundant. When power transitions from constraint to advantage, the discount rate narrows.

This is not theoretical. Capital allocators increasingly differentiate between markets where clean power is embedded versus engineered. Kenya sits firmly in the former category.

Sovereignty as a Revenue Multiplier

Data sovereignty is often treated as regulatory friction. In practice, it is now a revenue driver.

Kenya’s Data Protection Act and related localization provisions restrict where certain categories of data can be processed. Without a hyperscale-grade public cloud region, governments, banks, and regulated enterprises are forced into suboptimal architectures.

OCI Nairobi resolves that constraint. Entire classes of workloads that were previously blocked or delayed can now migrate locally. This demand is structural, not cyclical, and it supports longer contract tenors with lower churn.

For valuation, that matters. Sovereignty-driven demand behaves more like utility load than discretionary enterprise IT spend.

Platform Equity Replaces Project Equity

The ownership backdrop reinforces the repricing argument. iXAfrica is majority-owned by Helios Investment Partners, a sponsor with a proven track record scaling digital infrastructure across Africa.

Hyperscalers won’t anchor facilities backed by thinly capitalized sponsors they need balance sheets that can fund expansion, absorb delays, and maintain standards for decades.

This has a direct impact on capital structures.

Once a hyperscaler anchors a campus, development equity often transitions into platform equity. Debt capacity rises, the cost of capital falls, and exit options expand to include infrastructure funds, sovereign wealth, and strategic buyers.

That transition is what ultimately drives asset repricing.

This evolution toward platform equity is closely tied to sovereignty-aligned compute strategies, a dynamic examined in Where Sovereignty Meets Speed: The Rise of Sovereign Clouds and Edge Data Centers.

Regional Demand Changes the Market Math

Another underappreciated factor is geography.

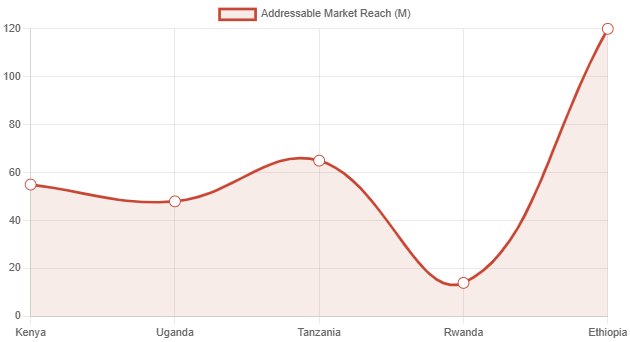

OCI Nairobi is not underwritten on Kenyan demand alone. It serves East and Central Africa, extending effective reach to more than 300 million people across Uganda, Rwanda, Tanzania, Ethiopia, and beyond.

Latency improvements across the region transform Nairobi into a hub, not a spoke. This regional multiplier allows hyperscalers to scale demand without replicating infrastructure in every market.

For investors, that creates operating leverage. Fixed infrastructure supports a larger addressable market, improving utilization curves and return profiles.

What Repricing Actually Looks Like

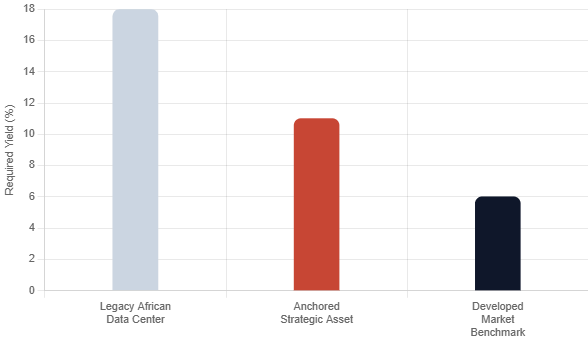

Repricing does not mean African data centers suddenly trade at Northern Virginia multiples. It means the spread narrows for specific assets with hyperscaler anchoring, credible power, and institutional governance.

Assets like iXAfrica’s Nairobi campus move out of the “emerging market speculation” bucket and into the “early-cycle hyperscale platform” category. That category attracts different capital, applies different underwriting assumptions, and tolerates lower headline yields in exchange for durability and growth.

Importantly, this repricing will not be uniform. It will be selective.

Markets without clean power, regulatory clarity, or credible partners will not benefit. Platforms without hyperscaler anchors will continue to face merchant risk. Capital will concentrate, not diffuse.

The Broader Signal to the Market

Oracle’s launch sends a message beyond Kenya: parts of Africa are now execution-ready for hyperscalers, as long as risk can be transferred to the right platforms. It validates the colocation-as-a-platform model and challenges assumptions behind African data center discount rates.

The takeaway isn’t that Africa has “arrived” it’s that the asset class is bifurcating. Some data centers remain speculative real estate plays; others, backed by hyperscalers and sovereign-aligned infrastructure, are priced as strategic infrastructure.

Oracle’s decision at iXAfrica draws that line clearly. The repricing has already begun.